Breaking the Cycle of Depression, Social Withdrawal, and Loneliness

Depression, social withdrawal, and loneliness often feed into each other, creating a vicious cycle that can feel impossible to escape. Research shows that social isolation worsens depressive symptoms, while depression, in turn, leads to further withdrawal (Cacioppo et al., 2006). When someone is depressed, they may isolate themselves, leading to loneliness, which in turn deepens the depression. Breaking this pattern requires awareness, intentional action, and self-compassion. In this article, we'll explore how this cycle works and practical steps to combat it.

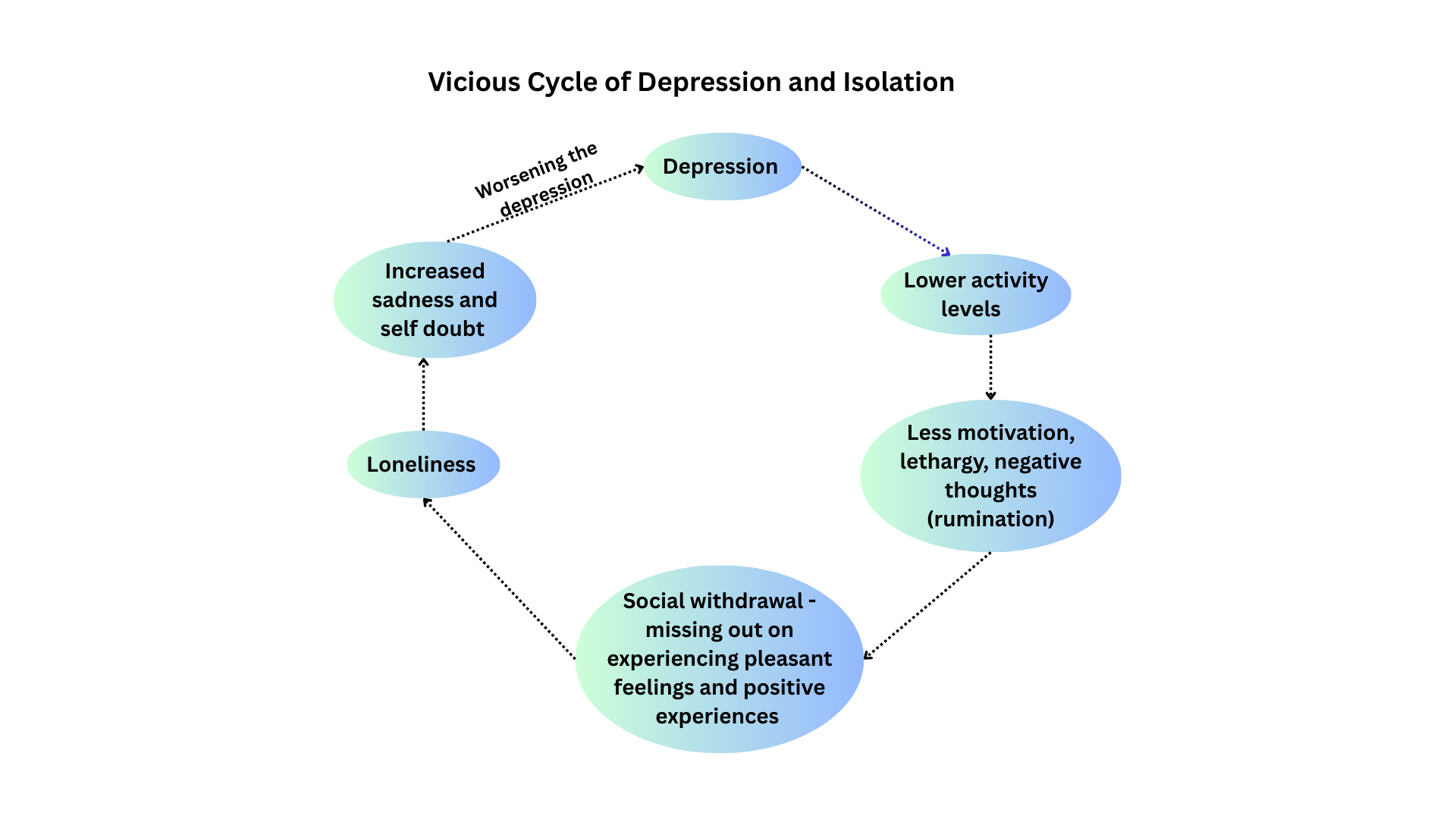

The Vicious Cycle of Depression and Isolation

Depression saps motivation, making social interactions feel exhausting or pointless. A person may cancel plans, avoid friends, or stop engaging in activities they once enjoyed. Over time, social withdrawal leads to loneliness, which reinforces feelings of worthlessness and hopelessness—key features of depression. The brain begins to interpret isolation as evidence that no one cares, further deepening the emotional pain (Cacioppo et al., 2006).

How to Break this Vicious Cycle

Start Small and Be Realistic with Social Re-engagement

Pushing yourself to attend a big gathering might feel overwhelming. Instead, begin with small social interactions daily:

Send a text to a friend

Join an online community related to your interests

Spend time in a public space (e.g., a coffee shop or park) where there is no pressure to interact with others.

Research supports that depressed individuals who scheduled weekly social outings experienced mood improvements within weeks (Jacobson et al., 1996).

Challenge Negative Thoughts

Depression often distorts thinking ("No one wants me around," "I'm a burden," "No one cares about me"). Counter these thoughts with evidence:

Is it really true that no one cares about you?

Would you judge someone else as harshly for needing support?

Exercise - A Natural Antidepressant

Physical activity can signal your brain to release feel-good endorphins. Endorphins are natural brain chemicals that can improve your sense of well-being. Physical activity increases endorphins and neurogenesis, countering depression (Schuch et al., 2016).

Routine

Isolation disrupts routines, worsening depression. Re-establish structure:

Set a consistent sleep schedule

Incorporate short walks—physical activity boosts mood

Schedule one daily "anchor" activity (e.g., reading, cooking)

Seek Professional Support

Therapy (e.g., CBT) can help break negative thought patterns. Support groups also provide connection with others who understand (Beck, 2011). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) significantly reduces depressive symptoms by modifying maladaptive thought patterns .

Practice Self-Compassion

Isolation often brings shame ("Why can't I just go out?"). Treat yourself as you would treat a struggling friend—with kindness, not criticism (Neff, 2003).

Final Thoughts

Breaking the cycle of depression and social withdrawal takes time. Progress may feel slow, but small, consistent efforts—like reaching out to one person or challenging a negative thought—can accumulate into meaningful change and rebuild confidence. If you're stuck, reaching out to a therapist can provide guidance. Remember: withdrawal is a symptom, not a personal failure. Each effort to reconnect is a step toward healing.

References

Beck, J. S. (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

Cacioppo, J. T., Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2006). Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: Cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychology and Aging, 21(1), 140–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.21.1.140

Jacobson, N. S., Dobson, K. S., Truax, P. A., Addis, M. E., Koerner, K., Gollan, J. K., Gortner, E., & Prince, S. E. (1996). A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(2), 295–304. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.64.2.295

Neff, K. (2003). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85-101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032

Schuch, F. B., Vancampfort, D., Richards, J., Rosenbaum, S., Ward, P. B., & Stubbs, B. (2016). Exercise as a treatment for depression: A meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 77, 42–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.02.023